Victoria Festival of AuthorsPoetry In Transit

With Dallas Hunt, Linda K. Thompson, Isabella Wang, and Terence Young

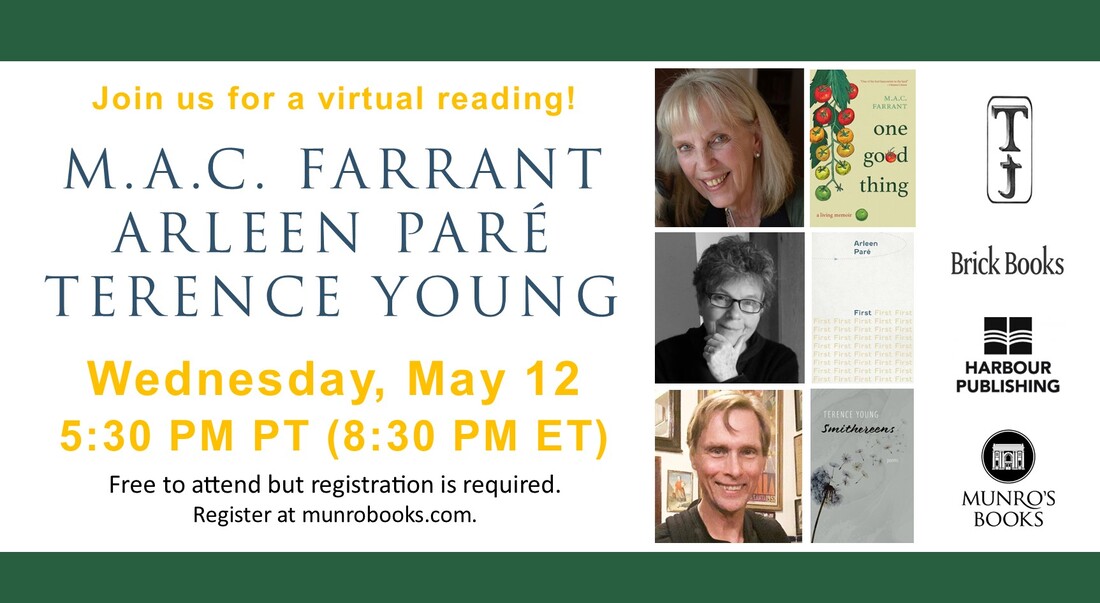

About this event Unique to the Victoria Festival of Authors, the fourth annual Forest Poet-Tree Walk places you in a West Coast landscape. This poetry reading under the trees unfolds at Mary Lake Nature Sanctuary in the Highlands. Surrounded by fir and arbutus, passing alongside creeks and the lakeshore, this is an immersive sensory experience. Led by Yvonne Blomer and Beth Kope, the poets Dallas Hunt, Linda K. Thompson, Isabella Wang, and Terence Young will offer their own explorations of landscape and memory. Their poems will illuminate, lament, and celebrate the natural world. Be prepared to walk, be prepared for any weather, be prepared to find the magic in the forest. Be aware that the audience may well include flickers, a heron, an otter, or mink. Curated and hosted by Yvonne Blomer and Beth Kope Captioning available for livestreamed event IMPORTANT NOTES: 1.) As this is an outdoor event, masks are not required, but they are encouraged and will be made available. 3.) Unfortunately, the in-person version of this event is not appropriate for those with accessibility needs. 4.) Please come prepared for all weather. This event is not weather-dependent. 4.) There will be no tickets available at the door. Ticket sales will end the day before the event. 5.) If you select to stream this event from home, the live-stream linkwill be emailed the day before the event. 6.) If you are unwell, please stay home. A Triple Launch at Munro's Books:

If you're thinking of attending, you will need to register here: Registration required

WHEREVER WE ARE GOING, WE ARE GOING TOGETHER: AN INTERVIEW WITH TERENCE YOUNG

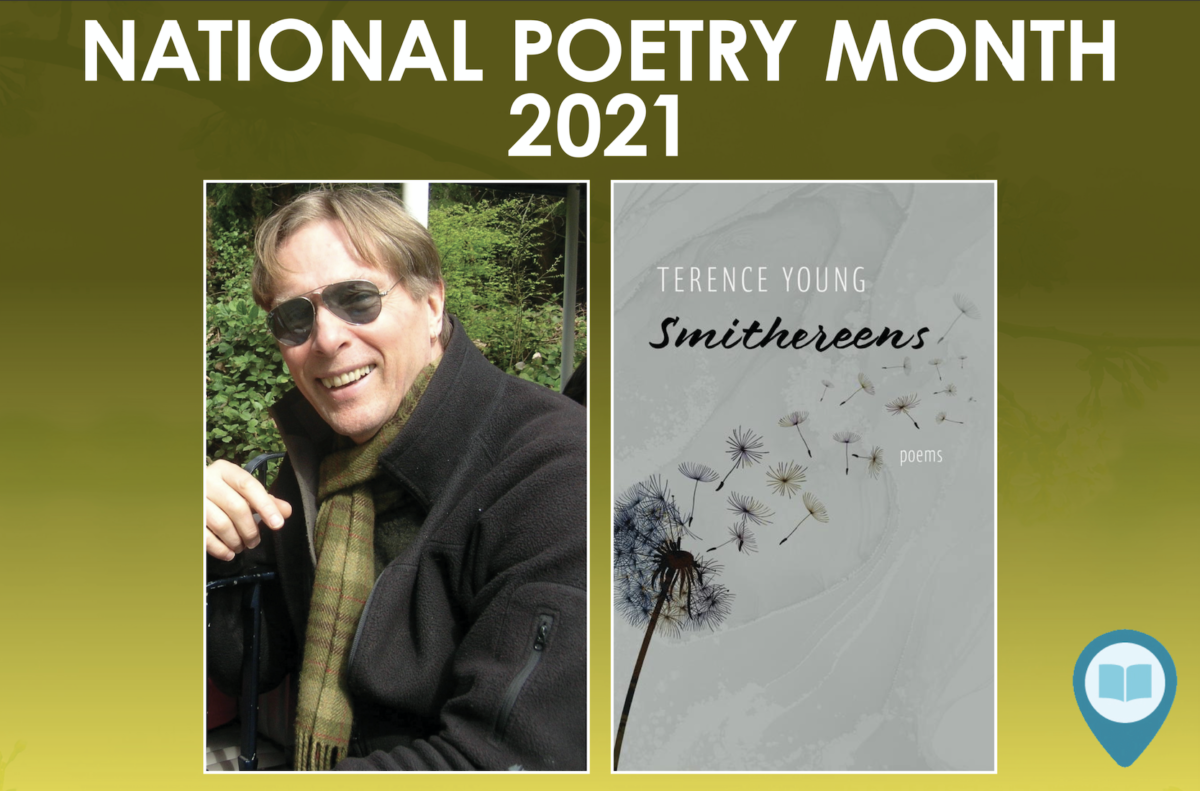

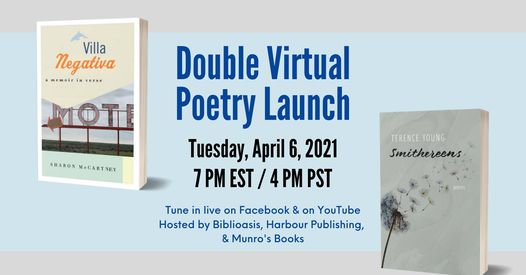

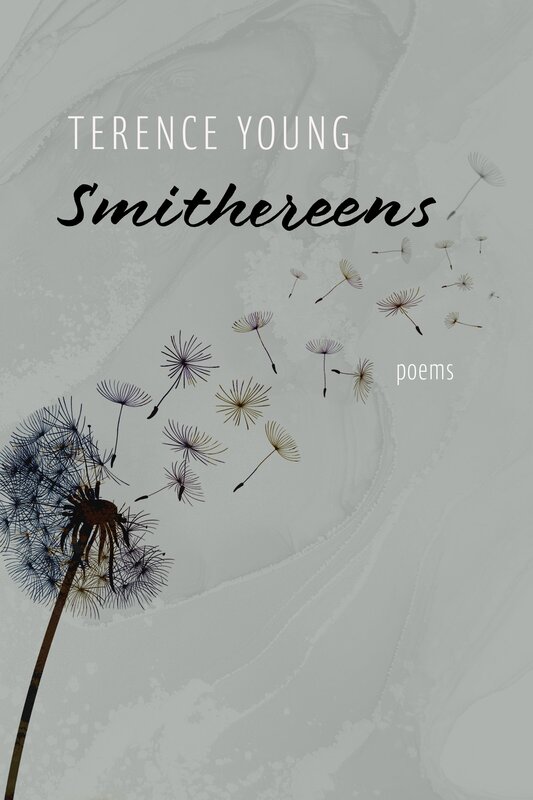

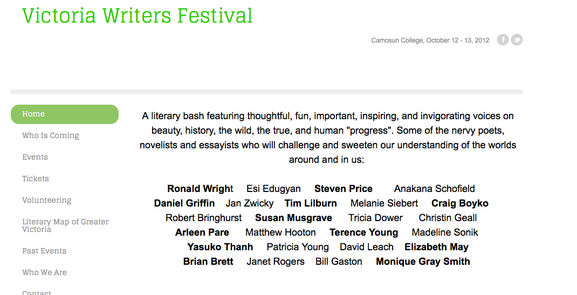

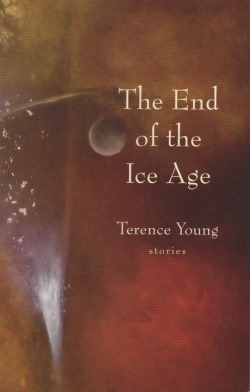

FEATURED INTERVIEW • APRIL 15, 2021 • ROB TAYLOR In addition to the interview above, here's one from March 5th, 2021, with Nathaniel Moore.Terence Young lives in Victoria, where he has recently retired from teaching English and creative writing at St. Michaels University School. He is a co-founder of The Claremont Review(1992), an international literary journal for young writers that has, after 25 years of service to the writing community, sadly closed its doors. His first book of poetry, The Island in Winter(Signal Editions, 1999), was shortlisted for the Governor General’s Award and the Gerald Lampert Award. Since then, he has published several books: a collection of stories, Rhymes With Useless (Raincoast, 2000), which was one of two runners-up for the annual Danuta Gleed award; a novel, After Goodlake’s, which received the City of Victoria Butler Book Prize in 2005; and a second collection of poetry, Moving Day (Signature Editions, 2006), which was nominated for both the Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize and The City of Victoria Butler Book Prize for 2006. In 2008, he was awarded the Prime Minister’s Award for Teaching Excellence, an honour shared with fifteen other teachers from across Canada that year. A second collection of fiction, The End of the Ice Age, was released from Biblioasis Press in the spring of 2010. He recently received a National Magazine Award (Silver) for his poem “The Bear.” Smithereens, his latest poetry collection, is now available from Harbour Publishing – Nathaniel G. Moore Nathaniel Moore: Your third book of poetry, Smithereens has garnered much attention from Canadian and International poets, including past winners of the Griffin Prize. What appears to be the consensus from this initial buzz is, your new poetry book is an engagement with humanity in time at all its stages, its delicate and complicated relationship with the physical world. As George McWhirter says, “Young attempts less to reconstruct a life, or lives, well lived than to enact a kind of verbal psychometry.” Instead of simply asking you what your new book is about, can you tell me, for reasons of personal curiosity, what was the first and last poem you wrote in this book? Terence Young: This book has been a while coming – my last collection came out in 2006 — so it’s hard to say which of the poems in Smithereens is the oldest, but if I had to guess I think it might be “Weight,” a poem that arose out my days working in a nickel mine in Thompson, Manitoba. The most recent poem is probably “Gathering,” a response to a recent visitation we had at our cabin, when a couple of dozen vultures descended into the woods not far away. Nathaniel Moore: Let’s give the reader a sneak preview of the book with the Manitoban poem you mention: Weight Let us recall people we have carried on our backs, like the girl this boy is hefting to prove he can, outside our local at closing, on a mid-November night thick with rain, both of them astonished by arms, thighs, to be so alive beneath their winter coats. Or the waitress I carried one December, across a snowy field in Thompson, Manitoba, sometime cook, too, in a coffee shop, generous with her portions of pancakes and eggs, lonely in a town of lonely people, out on her break that Christmas day, walking under the frozen northern sun in parka, thin shoes, me in boots and useless jeans, the snow deep enough to invite such a game, wondering as I did with almost every sympathetic face back then, was this someone to love, that whole mystery. But to get back to those kids outside the pub, as my wife and I walk by, the boy, his knees locked against buckling, the girl turning her head to smile at a cell phone, its flash lighting up the street, his face and behind him hers, stunned, joyous, bright echo of the photo someone took of the waitress, nameless now, and me, black and white study in self-consciousness, our two shadows crisp against the snow. Nathaniel Moore: Thanks, Terence. Every city and town in Canada has their own poetry community. From Moncton to Ottawa, Edmonton, to the Sunshine Coast in British Columbia, to Yellowknife in the Northwest Territories. For those not as familiar with poets in British Columbia, what would you suggest is the best way to get a crash course in what the poets in your province are doing? Terence Young: There are few ways to find out about BC writers in general. The first is to pick up a copy of BC Bookworld or have a look at it online. The Poetry section at The Ormsby Review also provides a quick access. After that, I’d suggest checking out The Federation of BC Writers. As a member, I find them extremely helpful with notifications about readings and literary news. They also have an extremely informative newsletter. In these times of Covid, it’s a little difficult to get out to readings, and festivals are currently online for the most part, but when they do come back, it’s always rewarding to attend The Vancouver Writers Festival, The Whistler Writers Festival, The Surrey International Writers’ Conference, and here in Victoria, The Victoria Festival of Authors. Nathaniel Moore: What are some poetry books you have in any given pile, bookshelf, or stack in your office or home? Terence Young: Recent additions include Outlasting the Weather by Patrick Friesen, The Essential Derk Wynand; and some that seem to pop up in the pile from time to time are Motherland, Fatherland, Homelandsexuals by Patricia Lockwood, Crush by Richard Siken, and Citizen by Claudia Rankine. Nathaniel Moore: Can you talk about the title — it’s a beautiful word on the page — a word we don’t see that often anymore. The delicate image on the cover seems to act in conflict with elements of what we associate with the word smithereens, yet, when you break it down, the wind comes, blows the dandelion into literally tiny pieces. Any thoughts on this design element? Terence Young: Smithereens is one of those wonderful words people generally discover as a kid. It has such momentum, such energy. It’s actually the last word in the poem “Easter Train,” from the collection, a moment when a young boy stops on a boulevard to pick the dandelions that have gone to seed and blow “to smithereens each and every one.” I love how Anna at Harbour pulled this one detail from the book to serve as the graphic complement to the title. Nathaniel Moore: Poetry and performance almost go hand in hand. With our planet’s current restrictions being in place for over a year now, how have you observed the way poetry is being presented, and how has this concerned or prepared you for the release of Smithereens? Terence Young: I’m actually fairly impressed by the way that writers and publishers have adapted to meet the challenge. Having attended several Zoom launches and readings over the past year, I am surprised to see how comfortable I am with the medium. So many more people can participate — time zones notwithstanding — and the audience can adjust the volume at will if they need to: sometimes a reader’s voice gets lost in the ceiling of some venues and there are often other sounds competing, like the steam of an espresso maker. Even better, viewers are not obliged to turn on their webcam and can watch the reading in their pyjamas if they like or take a quick trip to open another beer.Live readings will always be preferable, of course, but I’m wondering if these virtual readings might not become a fixture on the literary scene, given their audience reach and the option they provide not to have to drive any distance — you can see from my response that I have become one of Covid’s converts to introversion, which is another topic entirely. Nathaniel Moore: What do you hope readers will take away from reading Smithereens? Terence Young: As with any book of poetry, there will be poems that have no relevance for certain readers and others that will not appeal for reasons of style or content; but I hope that most readers will find some common ground in the book, as well as some language that meets with their approval and maybe even delights them. Nathaniel G. Moore is the author of seven books including Jettison (Anvil Press, 2013) Savage 1986-2011 (Anvil, 2013), winner of the 2014 Relit Award for Best Novel. His book reviews have appeared in the Georgia Straight, the Globe and Mail, and Canadian Literature, and he reviewed Scarred: The True Story of How I Escaped NXIVM, the Cult that Bound My Life, by Sarah Edmondson, for The Ormsby Review. He has also interviewed Curtis LeBlanc and Tom Wayman for The Ormsby Review. His new collection of essays, Honorarium, was released by Palimpsest Press (Windsor, ON) in Spring, 2021. Formerly of Pender Harbour, Nathaniel now lives and works in in Fredericton, New Brunswick. Most Anticipated: Our 2021 Spring Poetry Preview

Coming Soon!

This third collection of poetry will be available in Spring, 2021, from Harbour Publishing. The publishing info can be found here.

Daniel Scott of Planet Earth Poetry has worked hard to set up the Poets Caravan. Check out the info below and follow the link to see what he's been up to.

POETS CARAVAN

We are excited to launch our latest project to share poetry! The Planet Earth Poetry Poets Caravan highlights the rich cultural landscape of the CRD, with readings from poets in all of its nine regions. Each poet is represented by a pin on Google Earth of a spot meaningful to them in the CRD – somewhere they like to do their writing or find particularly inspiring. CLICK HERE TO GO TO GOOGLE EARTH & WATCH OUR POETS.(Be patient, the program needs a bit of time to load in your browser.) We have six CRD poets up; three more to come. After that, we’ll be adding more poets who live in Victoria, thanks to a grant from the City of Victoria.) The Poets Caravan is accessible to audiences both in the CRD and worldwide. This interactive experience will be available over time and provides a way for poets and poetry to reach a wide audience in this time when in-person reading events aren’t possible. Digital projects come with accessibility challenges for those who may not have access to a computer or have disabilities which stop them from using the selected platform. We have made the videos and text available for download separately on request. Please email Planet Earth Poetry if you’d like this option. Thank you to the CRD Arts and Culture Support Fund, the BC Arts Council and the City of Victoria for their support and funding of the Poets Caravan. Fresh New ShortsWriter John Blackmore has embarked on a great project: producing and presenting short stories written and read by a variety of authors. For anyone who is fond of podcasts and other online audio resources, this recent addition (the first was published in April, 2020) will be welcome. Most recent is a story by Erin McNair, "The Chemistry of Unhappiness," and the previous story is one of mine, "Parallax," first published in The Malahat Review. I highly recommend that you take some time to explore all the many offerings on the site. You won't be disappointed. You can find the site here: https://freshnewshorts.podbean.com

And, if you want to learn more about the world of story-telling podcasts, you can find the information you need at this location The Portland ReviewThe Portland Review, a literary magazine based in Portland, Oregon, at Portland State University, has recently published the story, "Nostalgia," and as promotion for their magazine, they have interviewed several writers about their work and its connection to the current issue's theme, labour. I include the interview below:

Writers at Work, Part II LEE WARE Contributors Share their Thoughts on Labor, Writing, and the Current ClimateWhile creating this issue, we thought about labor as both noun and verb, tangible and intangible. We discussed how labor is often hidden from view, how it can be private or public. How it can be an act of love or something that must be endured. Labor is often categorized—by type, by value—and that categorization can change with time and need as well as by who is doing the categorizing. And finally, we examined how labor contributes, for better or worse, to our identities and sense of self. In response to the latest edition of Portland Review, which features works on and about the idea of labor, Nonfiction Editor Lee Ware reached out to several of our contributors and asked them about the issue’s theme, their writing practice, and the impact the current climate is having on them. In this second of two posts, Lee spoke with contributors Catherine Esther Cowie, Emily Costantino, and Terence Young. Her previous conversation with Brian Evenson, Madeline DeLuca, and Nicole Melanson can be found here. Lee Ware: Describe your submission. How does it inform or represent your own thoughts about labor? Emily Costantino: Formally, I wanted to produce something that felt urgent, and free-associative. Like how someone thinks when they’re really tired and just want to go home. Just kind of scattered and longing. Catherine Cowie: I think labor is more than just an exchange of mental and physical exertion for pay. It includes our volunteer work, taking care of our families and attending to ourselves. Even the act of listening to a friend or a stranger is a form of emotional labor; restraining the tongue from offering advice, the mind from judgment or distraction, and simply holding space and attentively bearing witness to someone’s pain and joy. I would also suggest that our own grappling with our stuff whether through therapy or journaling is an act of emotional labor. At varying times, labor can demand more or less of our physical, mental and emotional energy. The poems I submitted reflect the physical and emotional exertion that is involved in caring for a loved one who is physically and mentally ill. Sometimes, the work is unpleasant and unwanted. And unfortunately, at times, children are given duties that one could argue should be given to an adult. How does this shape the child’s understanding of self? If the labor is unpleasant, and perhaps work that an adult should be doing, is the child’s self-esteem harmed? In the poem “Talk Therapy,” I wanted to show how emotional labor occurs in a family with a shared past of physical abuse. Recounting what has happened can be healing. However, depending on the recipient, recounting past hurts can potentially harm. If the recipient is a child, for example, receiving a story about a history of violence can create an emotional and mental burden. The story haunts the child. The child carries the weight of this story. Perhaps that is labor as well. On a subconscious level the mind is seeking to understand; why did this happen, what does this say about me and who I will become? Eventually this child, who will become an adult, might engage in more intentional emotional labor as they grapple to reconcile their sense of identity with their familial history. Terence Young: It’s hard not to think of Philip Levine’s collection What Work Is when discussing the idea of labor. He explores the subject so beautifully in those poems. For most of us, labor is a highly defined and highly monetized activity, one that tends to structure the way we see life. In my submission, “Nostalgia,” the narrator is an older man who has always seen his life as a series of jobs, whether they are part of his actual employment as a surveyor or the demands made on him as a husband, father, land owner. They are jobs he must complete, boxes he must tick, and he has difficulty being flexible, allowing others to engage the world less dutifully. The arrival of his grandson challenges him to re-examine his life, how he dealt with his daughter when she was young. The title derives from the condition that we now refer to as PTSD, the idea that the mind of a person who has been badly traumatized is compelled to return to the source of that pain, just as the narrator remembers his own father telling him at the dinner table that there will be no discussion about what there is to eat. “You’ll eat what you’re given,” he says, and in that moment even dinner becomes a job, a task to finish. LW: Where does your writing fit in relation to your thoughts about labor? EC: I like the word “co-constituted,” because it allows for things to come into being at the same time, relying on one another for existence. When things are co-constituted, it’s hard to trace their relationship because of their necessary dependence. Like, my writing will always necessarily reflect my class position, whether I acknowledge it or not. I think of this thing the poet and activist Judy Grahn said once about her epic poem, “A Women Is Talking to Death.” She said her writing will always reflect a “working class affect.” She didn’t say working class “ideology,” or even “spirit.” She said affect. In that, no matter the subject of Judy’s work, the working-class experience is always present in its feeling. It can’t be any other way. CC: Writing is a form of labor that I enjoy. It is both difficult and pleasurable. It demands mental and emotional exertion as I seek to discover and best represent/express emotional truths through poetry. There isn’t a lot of monetary value attached to writing poetry, but it is necessary work. Gregory Wolfe, in his essay, “The Wound of Beauty”, states: Beauty [art] allows us to penetrate reality through the imagination, through the capacity of the imagination to perceive the world intuitively… Art takes us out of our self-referentiality and invites us to see through the eyes of the other, whether that other is the artist herself or a character in a story. I believe this work, writing poetry, when done well, contributes to creating a more empathetic and compassionate world. Art can also be nourishing for both the creator and the recipient. There is a pleasure in bringing something to fruition. And there is a pleasure in consuming a well-crafted poem. Even if the content of the poem is heavy or sad, there is a beauty in the craft and how an emotional truth is conveyed that one can appreciate and enjoy. My hope also is that someone feels less alone. That their experience of life or the world is affirmed or validated in some way when they encounter my poems. TY: Writing and labor have been interconnected for much of my life simply because I made my living as a teacher of writing for many years. I have always felt that writing teachers should principally be writers who also teach rather than teachers who also write, but when the majority of one’s income derives from the day job, the distinction becomes quite blurred. Nevertheless, I feel it is important for students to see that their teacher is also submitting himself to the same demanding editorial scrutiny that he applies to them, and that he is taking the risks associated with the writing life, the risks of rejection, poor reviews or indifference. Writing itself can often feel like work, especially when it is going badly, but, on the other hand, work — all kinds of work — can feel invigorating, even joyous when it’s going well. We tend to reserve the word “work” for activities we find difficult or uninspiring or repetitive, but, in truth, work can be rewarding, especially when we are building something that will improve our own lives, building a house, digging a garden or composing a piece of music. One of the characteristics of writing is that it most often occurs outside the hours traditionally reserved for day jobs, so we tend to look on it as more of a recreation or hobby. But my wife has been a full time writer for most of her life, and our children grew up understanding that when she was writing, she was also working, that her work was important, more important than putting in a day at an office. LW: How is the current climate – specifically the stay at home and social distancing measures – affecting how you work and the type of labor you’re involved in? EC: I remember waking up in early March and watching the Dow drop by 3,000 points, my partner beside me staring at the ceiling in disbelief. After that day, I lost my three jobs within four days. Everything around me just disappeared or lost its value overnight. This happened to a lot of people in my life. But even against the backdrop of that uncertainty, I felt this irrepressible sense of relief. For the first time, maybe ever, I was told I didn’t have to work to be meaningful in the eyes of the state. It was like some kind of nod of approval from an absent father. CC: Right now, I work from home. Before COVID-19, I did the daily commute into the office. During this current climate, I am engaged in more emotional labor –checking in on friends, family and coworkers through email, phone calls and video chatting. I’ve also benefited from the emotional labor of others. TY: I retired from teaching three years ago, and in that time I have made the transition from a highly regimented and productive life to one in which I am free not to measure my days by how many papers I have marked, how many poems I have edited, how many textbooks I have ordered. The current restrictions, then, have not affected me as much as they have people who have been compelled to leave their employment, possibly forever. My work now is learning how to become the person I was before I joined the labor force, a person who sat and thought or listened to music or read or went for long walks without feeling irresponsible or unproductive. So far, I’m enjoying the job very much. LW: How have staying at home and social distancing impacted your writing practice? EC: I live in New York and I’m here because I find the pace of the city drives my creative practice. I write a lot on the train and in bars. The city being completely shut down has definitely changed the situations I write within. Now I’m usually stationary at my desk in the apartment I can’t afford and so I’m moving. CC: I have more time to work on my manuscript as well as more time to study writing with friends. A friend and I video chat once a week about poems that we like, why we like them and what can we learn in terms of craft from these poems. She picks up on certain things in the poem that I don’t and vice versa. It’s also interesting to see which poems she chooses for us to study. TY: For a lot of my time during the lockdown, I have been editing a book of poems that is due out next Spring. I am also working on a collection of short stories for submission to a press. As most writers are aware, the editorial process is one that never really ends, so the enforced attention to revision that the lockdown provides can be a little all-consuming, and at some point, I hope to tear myself away from it to work on finishing a novel I have been fiddling with for a few years now. Certainly, the lockdown has also served to increase the amount of time I spend reading, an activity that is as vital to a writer’s mastery of his or her art as putting words on paper. I must say that I am grateful to literary journals like The Portland Review for continuing to provide writers like me a place to place their stories and poems during these strange times, and in doing so provide fodder for other writers to pursue their own careers. LW: How do you think work and labor will change, or if you think it will, as we move forward and reopen local and global economies? EC: This is something I’ve been thinking about a lot. In the beginning I was terrified that everything would change forever, become unrecognizable. And now I’m more afraid of things just returning to business as usual. I think a lot of people are hoping their industries will undergo some kind of transformation after this is over. Even de Blasio’s new reopening “plan” for the city uses language like we will build a “better” and “more just” city. This economic crisis has once again exposed the inherent class inequality foundational to the American project. I’m stowing my pessimism by staying involved in community outreach projects, like the Covid Bail Out Fund. CC: I’m most interested in how organizations will treat their frontline workers—truck drivers, sanitation workers, factory workers, grocery store clerks. Will the value of these workers be recognized in more tangible and intangible ways? TY: I hope that we have realized that we are a vulnerable species, and that we need to have more safeguards in place to protect the weak and disadvantaged among us. I hope too that we have learned that economic success and excess are partly responsible for the situation we now find ourselves in. We have been living excessively for years, paying little or no attention to reinforcing the foundations of a just and safe state for all. Instead, we have cut social programs and financial support for the needy in pursuit of greater wealth for those who do not need it. Do we want to be a society that measures its worth by GDP and quarterly dividends or one that ensures the health and happiness of its citizens through accessible healthcare and housing and education? I also hope we now recognize how much we are dependent upon the workers in the poorest paid jobs such as agriculture, healthcare and the transportation of food, and that we will reward their contributions by giving them a decent living wage. I hope these things, but I am not hopeful that they will come about. Even though the narrator in my story seems to change by the end, most people tend to return to what is familiar, what is comfortable, and I think it will take much more than this current plague to set us on a new and better path. LW: How are you currently spending your time – working or otherwise? EC: I’ve put all my energy into starting this digital arts journal, The Quarterless Review. It’s an online platform featuring art being made in isolation. It came from an impulse to create a digital archive of how art is responding to, or somehow change by, the pandemic and growing economic crisis. We feature video, poetry, interview, performance art, or anything mixed media. Issues are released every week, as an attempt to document the evolution of things in real time. CC: Currently, I have the privilege of working my full-time job from home. I’ve taken up collage art as a hobby. I love cutting, ripping and gluing things together. A lot of YouTube and Facebook. Virtual poetry workshops. Hulu. Dancing to late eighties and early nineties music as well as best of world music Africa. I do long for more sunny days so I can take more walks. TY: Currently, I am doing as Voltaire advised, cultivating my garden. I am also, as are many among my friends, brewing beer and baking bread. Simple joys are the best joys, we are all learning. I hope we don’t forget. Emily Costantino is a poet and visual artist. She was the 2019 recipient of the Burton A. Goldberg manuscript prize through the Academy of American Poets. She lives in Brooklyn where she is working on a chapbook to be released later this year. Catherine Esther Cowie is a 2017 Callaloo Writing Workshop graduate. Her work has appeared in the Penn Review, Glass: A Journal of Poetry, Moko Magazine: Caribbean Arts and Letters, and Forklift Ohio. Currently, she resides in Illinois. Terence Young is the co-founder and former editor of the Claremont Review, an international literary magazine for young writers that has recently closed its doors after twenty-five years. “Nostalgia” is from his third but as yet unpublished collection of short stories, Parallax and Other Stories. He lives in Victoria, BC, and you can find more of his work at terenceyoung.ca. The Chestertown SpyDuring Poetry Month, The Delmarva Review is working in conjunction with The Chestertown Spy to post four poems from its current issue. I am happy to say that the poem "What We Keep" was chosen for the week of April 22nd.

|

|

Delmarva Review: What We Keep by Terence Young, April 22, 2020 by Delmarva Review Leave a Comment

From the Editor: Celebrating National Poetry Month, the Delmarva Review joins with Spy and poets from across the land to present an outstanding poem each week. This is the fourth poem from the review, with the poet’s comment for Spy’s discerning readers. Author’s Note: While I was teaching writing, I would encourage my students to love language and to explore words for their numerous nuances and applications, particularly in idiom. In “What We Keep,” I look at a relatively uninteresting verb and follow it in its many uses in regular conversation, and the result is not just a litany, but also a kind of narrative that compelled me to see the word differently. What We Keep The beat, the faith, the home fires burning. The people down, the good work up, the undesirables out, the grass off, the straight and narrow path to, all of it under wraps. The books, the peace, the house, the goal, certain fish, bad company, our heads when all about us are losing theirs. The change, we say, generous over nothing. Promises, sometimes, and secrets even when they no longer matter. Our opinions to ourselves. Time, if we understand music, quiet, if we don’t. Our children safe, our hands off the money, our friends close etc., a little something on the side. An eye out for strangers, a copy for our files, our shirt on and our big mouth shut. Fit, if we can, our fingers crossed. Our cards to our chest, a straight face when it all goes sideways. Our cool, our lips sealed, an open mind and our nose to the grindstone. The ball rolling, the wolf from the door. our powder dry. Terence Young is an author, former editor and teacher from Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. He co-founded and edited The Claremont Review, a literary magazine for young writers, and he was a teacher of English and creative writing at St. Michaels University School, in Victoria. His most recent book is a collection of short fiction, The End of the Ice Age (Biblioasis, 2010). Delmarva Review publishes the best of poetry, creative nonfiction, and short fiction selected from thousands of submissions annually from authors in the region, across the United States, and beyond. The independent literary journal is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit supported by individual contributions and a grant from the Talbot County Arts Council with funds from the Maryland State Arts Council. Print and digital editions are available at Amazon and other major online bookstores. Website: DelmarvaReview.org. |

River River Journal Issue #10

Read my poem "LookAt The Time" in River River Journal's Issue Number 10

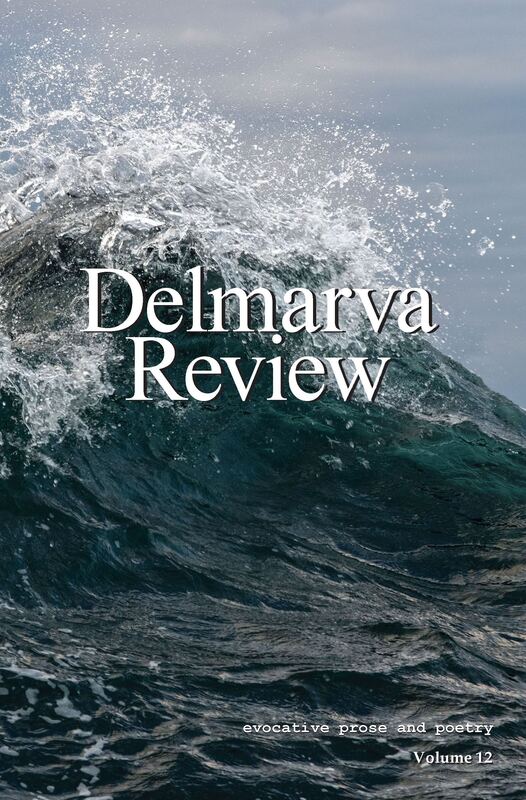

Delmarva Review -- Issue 12

This magazine from Maryland contains a poem of mine --- What We Keep --- from the current draft manuscript, Smithereens, which is due out with Harbour in 2021.

Black Horse Review

AT A LOSS FOR WORDS

TERENCE YOUNG

Spilled Milk Magazine --- Issue 10

Take a look at the online issue that features my story, "Offertory."

http://www.spilledmilkmagazine.com/issue-10

http://www.spilledmilkmagazine.com/issue-10

The Menteur -- Literary and arts magazine from the Paris school of arts and culture

This lovely online magazine accepted one of my poems for their 2019 issue. Follow the link to have a look at the magazine

https://thementeur.com

https://thementeur.com

Wandering into a Parallel Poetry Universe

with Terence Young: 2019 OV Contest Winner

Barb Carter, Lead Poetry Editor, in conversation with Terence Youngon his poem “Tender is the Night,” the overall winner of The Nick Blatchford Occasional Verse Contest for 2019. The poem appears in Issue 152 of The New Quarterly.

Barb: Terence, I can’t help asking what the term Occasional Verse means to you. What for you are the attributes of a well wrought occasional verse?

Terence: One could argue that all poems are occasional poems, in that some thought, some incident, some emotion serves as the occasion for the author’s sitting down to explore the experience. More traditionally, though, the occasional poem, at least in my understanding, arises out of a specific event, something that, at the time or latterly, acquires significance in the writer’s mind and merits articulation. Because there is often a narrative structure in such poems, the qualities of a good story apply. The reader likes to be engaged immediately, and the elements of the poem – the details, the tone, the imagery, the figurative language – should all contribute, as Poe suggests for the short story, to a single powerful effect. Helen Vendler, in her wonderful book, Poems, Poets, Poetry, spends an entire chapter on Keats’ “On First Looking Into Chapman’s Homer,” and her analysis not only helps students develop the skills that can help them look deeper into a poem, but also demonstrates how coherent and unified the language and structure of the poem truly are. In addition to these elements of technique, the reader must also be drawn to the voice of the poem, which may or may not be the voice of the poet. In Keats’ poem, we can feel the speaker’s astonishment and joy upon discovering Homer’s “wide expanse,” and I believe every good occasional poem should convey as much as possible of the poem’s emotional weight.

Barb: I began here because in reading over the adjudicator’s responses to your poem, I discovered that the late Nick Blatchford for whom the contest was created would have appreciated your poem, both for its humour and the fact that he oft quoted the line in Keats’ poem about stout Cortez on which your poem might be said to turn. Kim Jernigan, Blatchford’s daughter and contest creator, revealed that the fact that the poem’s comic effect is not a one-off joke is what would have made the poem appealing to her father. Is humour an essential characteristic to an occasional verse? Is there more to the back story that prompted you to write Tender is the Night than the poem suggests?

Terence: I don’t think that humour is essential to a successful occasional poem, but I think that it is essential for the poems that I write, in that I often find myself looking at the events of my life from a considerable height, a vantage point that allows me to see the ironies and the sometimes comic humanity of what transpires on this planet. The conjunction of everyday life with the magical is a great source for comedy – A Midsummer Night’s Dream comes to mind – but it takes perspective to isolate what such meetings reveal about us. Wordsworth, in the Preface to the Lyrical Ballads, talks about “emotions recollected in tranquillity.” He believed that a certain distance from events allowed him to see them better and more honestly. In the case of this poem, time tempered my initial disappointment at having to “wake up” and gave me the leisure to explore the fleeting joy of losing my bearings in a world where we rarely experience being lost. In that sense, the antecedents for “Tender is the Night” go back all the way to my youth when I would purposely choose the darkest path in the woods or no path at all, simply to feel what it was like not to know where I was. Once, after hours of such wandering in the dark hours past midnight, I actually came upon my own cabin, a kerosene lamp still burning in one window, and I failed to recognize the place, a moment that correlates exactly to the events of the poem.

Barb: Your poem is anything, but one-off. With its enticing literary allusions, both blatant and subtle, the poem stirs the reader’s imagination as well as tickles her intellect, encouraging the reader to discover as one judge suggested the wonder and majesty of a kid finding a “real secret passageway”. The reader is enticed to wander into your poem and through it into Keats’ On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer and into poetry’s appeal in general. The invitation to read your poem again and again and to return to Keats’ poem (or poems) is in that wonder. And yet, one never knows if the effect a poem has on its readers is intentional or spontaneous. Did you have a specific reader in mind when you wrote this poem?

Terence: I guess I would have to say that, if I imagine any kind of a reader – and in general, I don’t think that I do – it would have to be someone that is a lot like me. What I mean is that, for the most part, everything in my poems – the setting, the language, the allusions, the implied social perspective – can be traced quite easily to the kind of person who has been raised and educated in a fairly benign environment during a time of relative peace and prosperity. There are lot of people who will find little to connect with in what I write because their experience of this country, this world, this period in history bears little resemblance to mine, but, as we know, most people don’t read poetry, so I am not risking that much in the end. And, of course, the poem assumes that its reader will be familiar with a poet like Keats and with his exquisite renderings of our ambitions, our yearnings and our fears. In this litigious world, where one must pay huge sums merely to mention a line from a popular song or novel or poem, it is a little freeing to piggyback on the revelations of people like Keats and Shakespeare and Donne without the fear of being sued. A lot of what is appealing in works of literature is their intertextuality, and I am relying very much on this quality in my poem.

Barb: Tell me about the title of the poem. I think it is inspired.

Terence: Inspired it was, indeed, and once again it was Keats who provided the inspiration, not just for me, obviously, since F. Scott Fitzgerald used the same title for his brilliant novel about the Divers and their tempestuous marriage. In my case, the line from “Ode to a Nightingale” accurately conveys the pleasure of being deceived, of being “in the dark,” a state that Keats, in his poem, wishes would endure, if only to ward off the harsh reality of a world “where men sit and hear each other groan;/ Where palsy shakes a few, sad, last gray hairs,/ Where youth grows pale, and spectre-thin, and dies;/ Where but to think is to be full of sorrow.” My reasons for continuing the deception are less dire, a simple wish for there to be more of the magical, of the unexpected and unimagined, which are also everywhere in Keats’ poetry. “The Eve of St. Agnes” is a good example. In addition to the poem on Chapman’s translation of Homer and his “Ode to a Nightingale,” I also borrow slightly from his “Ode on Grecian Urn,” where he (or the urn) argues that “Beauty is truth, truth beauty – that is all/ ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.”

Barb: One might be tempted to take your poem lightly, a kind of shared musing about waking up disoriented and perhaps entering a parallel fantasy world, because of its casual free verse form and delightful contemporary diction (more like a kid who can’t believe/his room contains a real secret passage way, … when the woman next to me complains how late/ she’ll be now, thanks to this about-face…) but its deft lining and cleverly placed literary allusions confirm its depth. There seems to me an irony that this free verse poem by inserting midway and on its own a quotation from Keat’s Petrarchan Sonnet

(silent, upon a peak in Darien) corrals the reader into the world of poetry. Are you most often drawn to free verse when writing poetry?

Terence: Yes, absolutely, although I have experimented with forms like the palindrome from time to time, and I even invented a form much like the pantoum that relies on repetition for a cumulative effect. The bulk of what I write, though, is free verse, free in the sense that there is no predictable metre or rhyme. I tend to lean in my reading habits toward poets who make the art of writing seem clear and uncomplicated, as though they are simply speaking their thoughts as truly and engagingly as they can. I am thinking of poets like Tony Hoagland, Stephen Dunn and Philip Levine, among others, and in my own work it is this clarity and ease of entry that I strive for.

Barb: I liked too that one of the adjudicators was drawn to Tender is the Night because in his words it both lionizes and humanizes Keats. Keats is held high as a literary great, but he is revealed also to be a literal human. According to the poem, Keats preferred to scoff at the pedants and retain Cortez not Balboa as the one who first set European eyes westward from that mountain/ top because the latter name though accurate so spoiled the meter of his line. How can anyone resist a poet that to his death was certain that facts had little to do with truth or beauty? Methinks Terence, you make the difficult look easy. How many drafts were there before you submitted this final version? How do you know when a poem is complete?

Terence: Ha! That’s the first time I’ve been accused of that! Usually, I make the easy look difficult. The funny thing about being a writing teacher for so many years is that I rarely take my own advice. I’m just as unwilling as my students are when it comes to “killing my darlings,” and I often ramble on far longer than I should. Luckily, I live with a tough editor who is good at filtering out the dross. I also belong to a writing group. We meet once a month to share our poems. This particular poem has been hanging around for some time, and I have revisited it often, cutting a word or ten, rearranging line breaks, refining images. It will be included in my next collection, currently called Smithereens, which is coming out with Harbour Publishing in 2021. No doubt I will tweak it some more before that day arrives. More and more I am coming to believe that poems and stories are never really finished. Rather, it is the author who is finished pursuing perfection.

Barb: Terence, I can’t help asking what the term Occasional Verse means to you. What for you are the attributes of a well wrought occasional verse?

Terence: One could argue that all poems are occasional poems, in that some thought, some incident, some emotion serves as the occasion for the author’s sitting down to explore the experience. More traditionally, though, the occasional poem, at least in my understanding, arises out of a specific event, something that, at the time or latterly, acquires significance in the writer’s mind and merits articulation. Because there is often a narrative structure in such poems, the qualities of a good story apply. The reader likes to be engaged immediately, and the elements of the poem – the details, the tone, the imagery, the figurative language – should all contribute, as Poe suggests for the short story, to a single powerful effect. Helen Vendler, in her wonderful book, Poems, Poets, Poetry, spends an entire chapter on Keats’ “On First Looking Into Chapman’s Homer,” and her analysis not only helps students develop the skills that can help them look deeper into a poem, but also demonstrates how coherent and unified the language and structure of the poem truly are. In addition to these elements of technique, the reader must also be drawn to the voice of the poem, which may or may not be the voice of the poet. In Keats’ poem, we can feel the speaker’s astonishment and joy upon discovering Homer’s “wide expanse,” and I believe every good occasional poem should convey as much as possible of the poem’s emotional weight.

Barb: I began here because in reading over the adjudicator’s responses to your poem, I discovered that the late Nick Blatchford for whom the contest was created would have appreciated your poem, both for its humour and the fact that he oft quoted the line in Keats’ poem about stout Cortez on which your poem might be said to turn. Kim Jernigan, Blatchford’s daughter and contest creator, revealed that the fact that the poem’s comic effect is not a one-off joke is what would have made the poem appealing to her father. Is humour an essential characteristic to an occasional verse? Is there more to the back story that prompted you to write Tender is the Night than the poem suggests?

Terence: I don’t think that humour is essential to a successful occasional poem, but I think that it is essential for the poems that I write, in that I often find myself looking at the events of my life from a considerable height, a vantage point that allows me to see the ironies and the sometimes comic humanity of what transpires on this planet. The conjunction of everyday life with the magical is a great source for comedy – A Midsummer Night’s Dream comes to mind – but it takes perspective to isolate what such meetings reveal about us. Wordsworth, in the Preface to the Lyrical Ballads, talks about “emotions recollected in tranquillity.” He believed that a certain distance from events allowed him to see them better and more honestly. In the case of this poem, time tempered my initial disappointment at having to “wake up” and gave me the leisure to explore the fleeting joy of losing my bearings in a world where we rarely experience being lost. In that sense, the antecedents for “Tender is the Night” go back all the way to my youth when I would purposely choose the darkest path in the woods or no path at all, simply to feel what it was like not to know where I was. Once, after hours of such wandering in the dark hours past midnight, I actually came upon my own cabin, a kerosene lamp still burning in one window, and I failed to recognize the place, a moment that correlates exactly to the events of the poem.

Barb: Your poem is anything, but one-off. With its enticing literary allusions, both blatant and subtle, the poem stirs the reader’s imagination as well as tickles her intellect, encouraging the reader to discover as one judge suggested the wonder and majesty of a kid finding a “real secret passageway”. The reader is enticed to wander into your poem and through it into Keats’ On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer and into poetry’s appeal in general. The invitation to read your poem again and again and to return to Keats’ poem (or poems) is in that wonder. And yet, one never knows if the effect a poem has on its readers is intentional or spontaneous. Did you have a specific reader in mind when you wrote this poem?

Terence: I guess I would have to say that, if I imagine any kind of a reader – and in general, I don’t think that I do – it would have to be someone that is a lot like me. What I mean is that, for the most part, everything in my poems – the setting, the language, the allusions, the implied social perspective – can be traced quite easily to the kind of person who has been raised and educated in a fairly benign environment during a time of relative peace and prosperity. There are lot of people who will find little to connect with in what I write because their experience of this country, this world, this period in history bears little resemblance to mine, but, as we know, most people don’t read poetry, so I am not risking that much in the end. And, of course, the poem assumes that its reader will be familiar with a poet like Keats and with his exquisite renderings of our ambitions, our yearnings and our fears. In this litigious world, where one must pay huge sums merely to mention a line from a popular song or novel or poem, it is a little freeing to piggyback on the revelations of people like Keats and Shakespeare and Donne without the fear of being sued. A lot of what is appealing in works of literature is their intertextuality, and I am relying very much on this quality in my poem.

Barb: Tell me about the title of the poem. I think it is inspired.

Terence: Inspired it was, indeed, and once again it was Keats who provided the inspiration, not just for me, obviously, since F. Scott Fitzgerald used the same title for his brilliant novel about the Divers and their tempestuous marriage. In my case, the line from “Ode to a Nightingale” accurately conveys the pleasure of being deceived, of being “in the dark,” a state that Keats, in his poem, wishes would endure, if only to ward off the harsh reality of a world “where men sit and hear each other groan;/ Where palsy shakes a few, sad, last gray hairs,/ Where youth grows pale, and spectre-thin, and dies;/ Where but to think is to be full of sorrow.” My reasons for continuing the deception are less dire, a simple wish for there to be more of the magical, of the unexpected and unimagined, which are also everywhere in Keats’ poetry. “The Eve of St. Agnes” is a good example. In addition to the poem on Chapman’s translation of Homer and his “Ode to a Nightingale,” I also borrow slightly from his “Ode on Grecian Urn,” where he (or the urn) argues that “Beauty is truth, truth beauty – that is all/ ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.”

Barb: One might be tempted to take your poem lightly, a kind of shared musing about waking up disoriented and perhaps entering a parallel fantasy world, because of its casual free verse form and delightful contemporary diction (more like a kid who can’t believe/his room contains a real secret passage way, … when the woman next to me complains how late/ she’ll be now, thanks to this about-face…) but its deft lining and cleverly placed literary allusions confirm its depth. There seems to me an irony that this free verse poem by inserting midway and on its own a quotation from Keat’s Petrarchan Sonnet

(silent, upon a peak in Darien) corrals the reader into the world of poetry. Are you most often drawn to free verse when writing poetry?

Terence: Yes, absolutely, although I have experimented with forms like the palindrome from time to time, and I even invented a form much like the pantoum that relies on repetition for a cumulative effect. The bulk of what I write, though, is free verse, free in the sense that there is no predictable metre or rhyme. I tend to lean in my reading habits toward poets who make the art of writing seem clear and uncomplicated, as though they are simply speaking their thoughts as truly and engagingly as they can. I am thinking of poets like Tony Hoagland, Stephen Dunn and Philip Levine, among others, and in my own work it is this clarity and ease of entry that I strive for.

Barb: I liked too that one of the adjudicators was drawn to Tender is the Night because in his words it both lionizes and humanizes Keats. Keats is held high as a literary great, but he is revealed also to be a literal human. According to the poem, Keats preferred to scoff at the pedants and retain Cortez not Balboa as the one who first set European eyes westward from that mountain/ top because the latter name though accurate so spoiled the meter of his line. How can anyone resist a poet that to his death was certain that facts had little to do with truth or beauty? Methinks Terence, you make the difficult look easy. How many drafts were there before you submitted this final version? How do you know when a poem is complete?

Terence: Ha! That’s the first time I’ve been accused of that! Usually, I make the easy look difficult. The funny thing about being a writing teacher for so many years is that I rarely take my own advice. I’m just as unwilling as my students are when it comes to “killing my darlings,” and I often ramble on far longer than I should. Luckily, I live with a tough editor who is good at filtering out the dross. I also belong to a writing group. We meet once a month to share our poems. This particular poem has been hanging around for some time, and I have revisited it often, cutting a word or ten, rearranging line breaks, refining images. It will be included in my next collection, currently called Smithereens, which is coming out with Harbour Publishing in 2021. No doubt I will tweak it some more before that day arrives. More and more I am coming to believe that poems and stories are never really finished. Rather, it is the author who is finished pursuing perfection.

TNQ's Facebook Feed Nov. 11th, 2019

The New Quarterly: Canadian Writers & Writing

"imagining a new life, enchanted—I hope literally—about

to disembark on a foreign shore, perhaps in a parallel universe,

where every street is unknown, feeling a little like stout Cortez

in Keats’ poem, when he first sees the Pacific:

silent, upon a peak in Darien

though not as grand or literary, more like a kid who can’t believe

his room contains a real secret passageway, almost blinking and

rubbing my eyes to see if the mirage will disappear, which it does,

immediately, when the woman next to me . . . "

- Terence Young, "Tender is the Night"

This Featured Read of the Week continues at:

tnq.ca/story/tender-is-the-night

In another instance of serendipity, I have been invited to read at the Wild Writers Festival in Waterloo, which takes place during the brief few days I had already planned to spend in Ontario at Harbour Front, where Patricia is reading. I will be reading just before the opening event on the night of Nov. 1st.

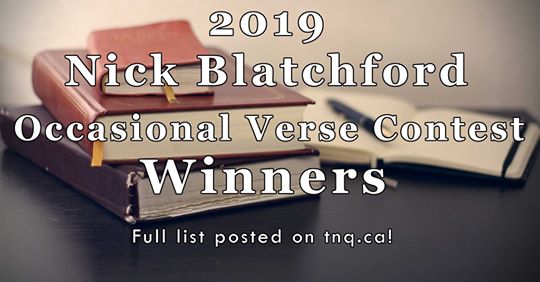

2019 Nick Blatchford Occasional Verse Contest Winners Winning Poem:

“Tender is the Night” by Terence Young

The poem will be posted here once it has been published in TNQ

Second Prize:

♦ “The Kindness of Port Angeles, 2002” by Deb O’Rourke

Third Prize:

♦ “First knock down” by Sarah Yi-Mei Tsiang

♦ “Transmission Tower” by Rob Taylor

♦ “Comrade Birds” by Frances Boyle

Honourable Mentions:

♦ “After the Wake” by Beth Downey

♦ “Letter to Whiskey” by Susan Vernon

♦ “Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy/Broken Heart Syndrome” by Laurie Koensgen

♦ “Shikata ga nai” by Lorin Jane Medley

♦ “In Winter” by Eleanor Sudak

♦ “Prologue to a Bliss State” by Lisa Martin

♦ “The Commons” by Rob Taylor

“Tender is the Night” by Terence Young

The poem will be posted here once it has been published in TNQ

Second Prize:

♦ “The Kindness of Port Angeles, 2002” by Deb O’Rourke

Third Prize:

♦ “First knock down” by Sarah Yi-Mei Tsiang

♦ “Transmission Tower” by Rob Taylor

♦ “Comrade Birds” by Frances Boyle

Honourable Mentions:

♦ “After the Wake” by Beth Downey

♦ “Letter to Whiskey” by Susan Vernon

♦ “Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy/Broken Heart Syndrome” by Laurie Koensgen

♦ “Shikata ga nai” by Lorin Jane Medley

♦ “In Winter” by Eleanor Sudak

♦ “Prologue to a Bliss State” by Lisa Martin

♦ “The Commons” by Rob Taylor

National Magazine Award (Silver)

Here is the "The Bear," which was both a winner in the TNQ's Occasional Verse contest of 2018 and a Silver finalist in the National Magazine Awards, 2019. Following it is an interview conducted by Kim Jernigan of The New Quarterly about the poem.

The Bear

Woken from an afternoon nap, you rise only to descend your wood-

butcher stairway, past the vaulted, multi-mullioned window on whose

other side now sits a bear, Buddha-like, on his backside, head concealed

in the Rubbermaid garbage can he holds aloft between two paws.

In sixty summers you’ve never seen such a creature anywhere near

this place, found no scat, heard no tales of neighbours’ fruit trees

bent or broken, undaunted for all this time to ramble, kids in tow,

down the remnant logging roads and deer paths that make a park

of these toy woods, so close to town now town has devoured all the

land between. Yet, here he sits, or she, for all you know, fur so black

it’s almost blue, only thin glass between you, so suddenly proximate

you are pressed to say what you are seeing, this vaudeville act, ursine

slapstick Chaplin who invites you to forget all danger, to forget you

are still one animal coming upon another. A single noisy tread, one

tell-tale stair, and you are busted, as the beautiful comedian detects

your gaze behind the fifteen panes that transform bear to cubist

caricature, your clown of darkness, who regains all fours, and turns

literal tail to amble, not run, back into the maze of forest and con-

spiratorial salal, but not before you throw sense and caution to the

wind, wrench open the back door and follow at a distance, axe in

hand, berating your bruin-buffoon for transforming forever this be-

nign acreage into something less safe, if more magical, where visiting

spirits leave behind their perfect signature, which, to all who will

listen over dinner and wine, you reveal with a flourish at the tale’s

end, the garbage can’s rectangular lid and four neat punctures,

arranged in a fan, an arc, like a winning hand of poker, jokers wild.

Exploring Occasion: An Interview with Terence Young

by Kim Jernigan with Terence Young

Kim Jernigan in conversation with Terence Young on his poem “The Bear,” one of the winners in The Nick Blatchford Occasional Verse Contest for 2018. The poem appears in Issue 148 of The New Quarterly.

Terence Young is a poet and fiction writer who lives on Vancouver Island where, until his recent retirement, he taught English and Creative Writing at St. Michaels University School. He is co-founder of The Claremont Review, an international journal for young writers, as well as an accomplished writer himself—and an inspired and inspiring teacher.

In 2008, he was awarded the Prime Minister’s Award for Teaching Excellence, a national honour. “That Time of Year,” a story from his second collection of fiction, The End of the Ice Age, was selected for the annual Best Canadian Stories in 2012. The whole family is literary (his wife, the poet Patricia Young, has frequently been among the finalists for the Occasional Verse contest). The setting for his poem “The Bear” is taken from life, a property that has been in his family since the 19th century. The land, a small acreage, includes a barn that has been transformed over the years into a summer cabin, complete with cast iron bathtub, outdoor shower, and a 1939 Savoy Enterprise wood cook stove.

*

Kim Jernigan: When I wrote to tell you that “The Bear” was one of the winners in The New Quarterly’s Occasional Verse contest, you replied, “I have only recently returned to writing poetry more seriously and am a little uncertain about it. The contest, centred as it is around occasional verse, suits what I write perfectly, since I am by nature drawn to the lyrical narrative.” I know you’ve worked primarily in the short fiction genre and am curious to know how you understand that term in relation to both fiction and poetry.

Terence Young: Having been a teacher of English literature for far too long, I understand the term “lyric” as it pertains to poetry that is primarily the expression of emotion, usually written in the first person. Shakespeare’s sonnets are good examples, as are odes and elegies. Narrative poetry usually takes the form of ballads, epics, and romances. Coleridge and Wordsworth threw this distinction out the window when they published the Lyrical Ballads in 1798.

My first poetry teacher, George McWhirter, applied the term “lyrical narrative” to the kind of poetry I was writing for him while I was at UBC in the MFA program there, and I think it has always rung true. I tend to explore “occasions” for meaning, for personal significance, and because these occasions are often incidents, they end up taking the form of a story, one that, in its language, tries to convey not only a narrative, but also a tone: the attitude of both the speaker and the author. My impression is that such poetry is of less interest for readers of verse these days and that the musicality of language detached from any story is in the ascendant.

I read all kinds of poetry and am continually amazed by what I read, but when I write, it is usually the lyrical narrative that finds its way onto the page. As for fiction, story is still an important component, although there is a multiplicity of ways to tell stories, techniques that involve the manipulation of voice, chronology, setting, diction, point of view. Like many writers, I don’t really know exactly where I am going when I begin a story and am often surprised where I end up. But, as with my poetry, the effects of tone, language, and the tale’s structure really dictate the success of the final product.

KJ: The New Yorker, in their fiction issue of some years back, divided their pick of the best up-and-coming writers into categories by subgenre, one of which they dubbed “lyrical realism,” stories taken from life in which the language, particularly the imagery, lifted, or dignified, the subject matter. Think Joyce’s “The Dead.”

Yet your fiction, at least in The End of the Ice Age, seemed to me darker, grittier, more despairing. Then I came upon “That Time of Year,” a story about a long marriage, about aging, diminishment, and loss, which none the less lifted and comforted me. It begins, beautifully,

They swam on the last night of summer. The lake still held the heat of the day, and in the fading light bats swooped low over the water, hunting the few remaining mosquitoes. Tomorrow’s forecast was for clouds, possibly showers. There was a note of loss in the air, as there always was when the weather turned. It wasn’t just another rain coming. It was the shrinking year, the dark months, the retreat from joy. How many times could she do this, she wondered. It was like drowning. She almost laughed at the thought, afloat as she was on her back, looking up at the stars that multiplied in the deepening sky. But, no, that was exactly what it felt like. It was like going under.

I’m pretty sure the ghost of “The Dead” hovers over this sad/luminous story. Or maybe the voice of Virginia Woolf in To the Lighthouse? Whom would you put forward as your literary mentors?

TY: The story you have quoted takes its title from Shakespeare’s sonnet 18: ‘That time of year thou may’st in me behold/ when yellow leaves, or none, or few do hang.’ And, like “The Bear,” it is situated at our cabin, a similarity that demonstrates just how strongly that little piece of land figures in my life and the lives of my family. What I like about Shakespeare’s sonnet is the voice, the calm and honest speaker who offers three distinct images of his stage of life, each an image of approaching extinction, and how he argues rationally and forcefully that it is this transitory quality that should bind us even more closely to one another.

It is a lovely thing to stumble upon a character whose musings allow the writer to explore at his or her leisure such pressing questions. Certainly, Joyce in The Dubliners has a number of such voices, as does Woolf in her stream of consciousness meanderings. I am also drawn to the people in Haruki Murakami’s stories and novels, particularly the speaker in his novel Norwegian Wood. I even tried consciously to copy Murakami’s style for a couple of stories, so strong was the impression he made upon me. There are many other writers who have influenced how I write: Joy Williams, Lorrie Moore, Amy Hempel, Amy Bloom, Denis Johnson, Tobias Wolff. More recently, I am drawn to the clarity of someone like Rachel Cusk, who mixes fact and fiction so brilliantly, but also to the zaniness of writers like Karen Russell and Lauren Groff.

KJ: Every year the judges of the OV contest, friends and family of the man for whom it’s named, wrestle with the question, “What is Occasional Verse?” We’ve settled on two loose criteria: there must be an occasion, of course, and the poem should be addressed in some way.

Our sense of what constitutes an occasion is open-ended. Many of the poems received were written for a formal occasion: a wedding, a birth, an anniversary, a funeral. But others make an occasion of something ordinary by virtue of the poet’s attention. Examples from this year’s gathering: a man sweeping snow off a rooftop antennae, a child responding to his father’s query about what he dreamt that night, a mother doing a crossword puzzle with her grown daughter. The addressee of the poems (we often imagine these poems being read aloud, and indeed read them aloud ourselves as part of the adjudication process) is sometimes made explicit, as in Suzanne Nussey’s “For My Husband on Our Anniversary,” but other poems are addressed slant: to a daughter, to another poet, to a civic “we”, or to the dead.

Your poem “The Bear” takes as its occasion a bear raiding a garbage can on a wooded lot that’s long since been encroached upon by the city. Sighting a bear where you don’t expect one is an occasion, for sure, a brush with mortality, but the chief interest in your poem, or so it seems to me, is as much in the addressee, “you,” initially some version of the poet’s own self. But there’s a nifty shift at the end from the poet registering his experience as it unfolds to his imagining how he will polish the story for sharing later around the dinner table.

My father, after whom the contest is named, was a natural raconteur. I was always amazed, listening to him tell a story about an adventure I’d been party to, at how much more wonderful, meaningful, or apt the story was in his telling. Do you also rise to an audience, or do you prefer the distancing mechanism of the page? A little of both? You are, of course, a teacher as well as a writer, but what was, for you, the added value of concluding the poem with that imagined retelling, a second occasion to cap the first?

TY: I’m pretty sure many people, despite whatever inconvenience, danger, annoyance they may be experiencing at the time, consider the possibility of embellishing the episode later to a friend or friends around a dinner table or at the pub. We are very “meta” in that regard, both living our lives and imagining at the same time how others, even ourselves, may view them later. Facebook and the art of the selfie may be to blame for the latest obsession with how our exploits are perceived, but I have no doubt that the storyteller in all of us and his or her penchant for elaboration has been with us for a long, long time.

It’s also interesting that some stories do not lend themselves to such artistic interpretation. My father loved to tell stories, for example, but he would never speak of the war. Clearly, it needed no enhancement and was something he preferred to forget. Like my father, I also love to tell stories, and teaching was a great vehicle for combining literature and personal experience. I once had a student come back to tell me many years later that a story I once told about my high school years, during which several of us at one point dared another student to jump out the math class window when the teacher’s back was turned, had actually gained some personal significance for her, for she had married the son of the jumper. The connection did not become clear until she innocently brought up my story at dinner one night, and her new father-in-law, astonished to hear about the incident so many years after the fact, revealed that that story was actually about him, attested to its truth and to the fact that he had broken both ankles upon hitting the ground. So, yes, I do indeed rise to an audience, and the poem about the bear has been told many times with many variations and emphases.

For me, the conclusion of the poem seems in keeping with magical qualities of the bear itself, that the appearance of such a creature in a place where none had been seen for over half a century should rightfully become the stuff of legend. And what better way for a legend to start than among friends during a meal.

KJ: I’m also interested in how you conceived of the character of the bear, a combination of clown and adversary.

TY: Rightly or wrongly, when I first saw him, it was hard to think of the bear as anything other than comical, seated as he was with his head in the plastic garbage can. He might have been an act from the circus, he looked that silly. Close as I was, too, I was able to see quite clearly how lustrous his fur was, what a young and handsome creature he was. Having worked in the bush, however, I knew also that it was not wise to anthropomorphize these animals, that they are unpredictable and powerful. And I was instantly aware that something had changed, that the mere sight of him had altered the woods around us.

KJ: So many of the poems received for this contest concern issues or life experiences that bring up emotion on tap. So we are always asking ourselves where is the craft? To what extent is the impact of a poem owing to the poet’s handling of form and language as opposed to the claim of the occasion itself? Can you speak to some of the techniques you used to shape the story you wanted to tell, or perhaps to understand, yourself, its significance, in the moment and after?

TY: I have to say that I’m not really conscious of technique when I am writing. I’m mostly looking for the right form—in this case the couplet—and the narrative flow of the poem, how it moves from moment to moment. I’m also trying to identify exactly what it was about the experience that affected me. To see a bear is one thing, but to see one in such proximity after a sleep when one is still in partial dream state is a different thing entirely, and if there is anything worthwhile in a poem, it must come from a true rendering of the emotions and thoughts that generated it.

KJ: I appreciate what you are saying, that if the form is too insistent, too self-conscious, the whole thing can collapse under its own contrivance. But I still can’t help but admire how “The Bear” works: the couplets are a visual equivalent of the opposed realities—man and bear. But lest that become facile, only the first two—when taken together, a kind of establishing shot—are end stopped. The next sentence runs a little over five lines, ending mid-line, as also the third. But the fourth and final sentence runs to twelve lines, a great rush of words that, subliminally at least, suggests the adrenalin rush of the encounter.

Then there’s the poem’s ending. Earlier, you included Lorrie Moore in your list of writers whose work informs your own. She has said that “[t]he end of a story is really everything.” It’s often not the chronological ending, “but it gives the whole meaning to the story.” I think the same could be said of a poem, so I felt a particular joy at imagining the ah-ha! moment when your raconteur self seized upon the perfect simile with which to end his story, a description of “…the garbage can’s rectangular lid and four neat punctures, / arranged in a fan, an arc, like a winning hand of poker, jokers wild.” Jokers wild! That’s the experience in a nutshell, the poet’s cautionary note to self: a bear, no matter how clownish he looks, can snuff out a life with the swipe of a paw.

Okay, two last questions: The initial encounter ends with the narrator/poet following the bear “axe in hand.” So I have to ask, “What the heck were you thinking of doing with that axe?!!” And what are you thinking of doing with your prize money?

TY: As for the axe, some part of me was aware that Trisha was down the road gathering blackberries, and I think I felt I had to arm myself in case he headed in that direction. After he disappeared, I ran as fast as I could to where Trish was and did my best to convince her calmly that she needed to return to the cabin. The axe was still in my hand, so I believe she picked up on my urgency.

The prize money, on the other hand, no longer exists, which is to say that I spent it as soon as I heard about the poem’s success. Since our most recent indulgence was a trip to Spain and Portugal in September and October, I think it’s safe to say that it helped us to more than a few delightful Spanish and Portuguese meals, possibly even some wine.

Here is the "The Bear," which was both a winner in the TNQ's Occasional Verse contest of 2018 and a Silver finalist in the National Magazine Awards, 2019. Following it is an interview conducted by Kim Jernigan of The New Quarterly about the poem.

The Bear

Woken from an afternoon nap, you rise only to descend your wood-

butcher stairway, past the vaulted, multi-mullioned window on whose

other side now sits a bear, Buddha-like, on his backside, head concealed

in the Rubbermaid garbage can he holds aloft between two paws.

In sixty summers you’ve never seen such a creature anywhere near

this place, found no scat, heard no tales of neighbours’ fruit trees

bent or broken, undaunted for all this time to ramble, kids in tow,

down the remnant logging roads and deer paths that make a park

of these toy woods, so close to town now town has devoured all the

land between. Yet, here he sits, or she, for all you know, fur so black

it’s almost blue, only thin glass between you, so suddenly proximate

you are pressed to say what you are seeing, this vaudeville act, ursine

slapstick Chaplin who invites you to forget all danger, to forget you

are still one animal coming upon another. A single noisy tread, one

tell-tale stair, and you are busted, as the beautiful comedian detects

your gaze behind the fifteen panes that transform bear to cubist

caricature, your clown of darkness, who regains all fours, and turns

literal tail to amble, not run, back into the maze of forest and con-

spiratorial salal, but not before you throw sense and caution to the

wind, wrench open the back door and follow at a distance, axe in

hand, berating your bruin-buffoon for transforming forever this be-

nign acreage into something less safe, if more magical, where visiting

spirits leave behind their perfect signature, which, to all who will

listen over dinner and wine, you reveal with a flourish at the tale’s

end, the garbage can’s rectangular lid and four neat punctures,

arranged in a fan, an arc, like a winning hand of poker, jokers wild.

Exploring Occasion: An Interview with Terence Young

by Kim Jernigan with Terence Young

Kim Jernigan in conversation with Terence Young on his poem “The Bear,” one of the winners in The Nick Blatchford Occasional Verse Contest for 2018. The poem appears in Issue 148 of The New Quarterly.

Terence Young is a poet and fiction writer who lives on Vancouver Island where, until his recent retirement, he taught English and Creative Writing at St. Michaels University School. He is co-founder of The Claremont Review, an international journal for young writers, as well as an accomplished writer himself—and an inspired and inspiring teacher.

In 2008, he was awarded the Prime Minister’s Award for Teaching Excellence, a national honour. “That Time of Year,” a story from his second collection of fiction, The End of the Ice Age, was selected for the annual Best Canadian Stories in 2012. The whole family is literary (his wife, the poet Patricia Young, has frequently been among the finalists for the Occasional Verse contest). The setting for his poem “The Bear” is taken from life, a property that has been in his family since the 19th century. The land, a small acreage, includes a barn that has been transformed over the years into a summer cabin, complete with cast iron bathtub, outdoor shower, and a 1939 Savoy Enterprise wood cook stove.

*

Kim Jernigan: When I wrote to tell you that “The Bear” was one of the winners in The New Quarterly’s Occasional Verse contest, you replied, “I have only recently returned to writing poetry more seriously and am a little uncertain about it. The contest, centred as it is around occasional verse, suits what I write perfectly, since I am by nature drawn to the lyrical narrative.” I know you’ve worked primarily in the short fiction genre and am curious to know how you understand that term in relation to both fiction and poetry.

Terence Young: Having been a teacher of English literature for far too long, I understand the term “lyric” as it pertains to poetry that is primarily the expression of emotion, usually written in the first person. Shakespeare’s sonnets are good examples, as are odes and elegies. Narrative poetry usually takes the form of ballads, epics, and romances. Coleridge and Wordsworth threw this distinction out the window when they published the Lyrical Ballads in 1798.

My first poetry teacher, George McWhirter, applied the term “lyrical narrative” to the kind of poetry I was writing for him while I was at UBC in the MFA program there, and I think it has always rung true. I tend to explore “occasions” for meaning, for personal significance, and because these occasions are often incidents, they end up taking the form of a story, one that, in its language, tries to convey not only a narrative, but also a tone: the attitude of both the speaker and the author. My impression is that such poetry is of less interest for readers of verse these days and that the musicality of language detached from any story is in the ascendant.

I read all kinds of poetry and am continually amazed by what I read, but when I write, it is usually the lyrical narrative that finds its way onto the page. As for fiction, story is still an important component, although there is a multiplicity of ways to tell stories, techniques that involve the manipulation of voice, chronology, setting, diction, point of view. Like many writers, I don’t really know exactly where I am going when I begin a story and am often surprised where I end up. But, as with my poetry, the effects of tone, language, and the tale’s structure really dictate the success of the final product.

KJ: The New Yorker, in their fiction issue of some years back, divided their pick of the best up-and-coming writers into categories by subgenre, one of which they dubbed “lyrical realism,” stories taken from life in which the language, particularly the imagery, lifted, or dignified, the subject matter. Think Joyce’s “The Dead.”